Saturday, April 05, 2008

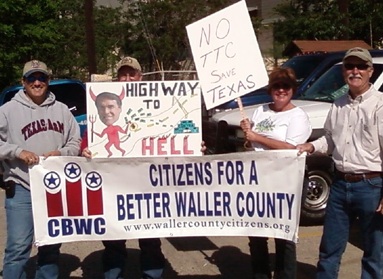

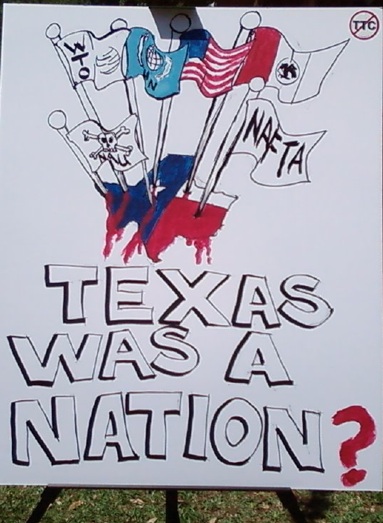

STOP THE TTC & TOLLS ACROSS TEXAS RALLY

TEXAS

Come and take it back.Saturday, APRIL 5th

Rally at the Capitol from 1:00 pm - 4:00 pm

Meet in the parking lots at the corner of Hwy 343/Ceasar Chavez St. & Red River St. (one block west of I-35). Click Here for map .

Sponsored by: Texans Uniting for Reform and Freedom

To search TTC News Archives click

"Articles and editorials relating to the Waxahachie Daily Light's anti-TTC coverage were taken off."

King of Spain 'owns' Waxahachie Daily Light

Demotion, removal of anti-TTC articles cause stir

April 4th, 2008

Ellis County Press

Copyright 2008

WAXAHACHIE – Residents researching the Waxahachie Daily Light website in hopes of finding articles on the Trans-Texas Corridor were recently surprised to find they had been removed.

Would this be because Macquarie Media Group, ( based out of Australia) the WDL’s new corporate owners, have strong ties with the TTC?

Some political observers and journalists believe Macquarie – whose principal partner is Spanish King Juan Carlos – is a key player in the consortium to build the North America's SuperCorridor Coalition, starting first with Gov. Rick Perry’s Trans-Texas Corridor, a network of private toll roads and high-speed highway lanes that will parallel the state’s current interstate highway system.

The same observers who reported on the media buyout of the WDL and 39 other papers – including the Ennis Journal, Italy News-Herald, Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Chronicle – believe Macquarie is silencing opposition to the TTC. Macquarie and King Carlos are investors in the TTC.

Neal White, who was demoted to editor after the buyout, told The Ellis County Press “We've been leading the state in coverage and will continue to do so.”

Jeremy Halbreich, the president of American Consolidated Media, the Dallas-based media firm Macquarie bought, said the media firm would not have a direct influence over what its member papers cover.

“No in any way, shape or form,” he said.

Having managed The Dallas Morning News for 10 years, Halbreich said he strongly respects reporters and what they do.

“ There is no interlocking directors or connections at all,” said Halbreich. “The firm is two separate companies.”

Allegations that ACM was siding with one side over the other was characterized by Halbreich “absolutely ridiculous if not insulting.”

Halbreich said his papers try to cover both points of view, but if Ellis County readers had questions, he said he would be happy to talk with them.

When The Ellis County Press called in reference to the missing TTC articles on the WDL archives, representatives of the paper said their website hosting switch in December was the cause of certain articles missing.

However, archived articles relating to various local issues were found. Articles and editorials relating to the WDL’s anti-TTC coverage were taken off.

Two different reporters for this paper conducted searches over the span of a month. When notified of this, ACM manager Jeremy Halbreich said the reporters might have been performing the searches incorrectly.

After the WDL was contacted about the situation, The Ellis County Press was able to find the once-missing archives.

“Must've been the flip of a switch,” Halbreich said. The site is now showing over 200 results from the past 744 days.

© 2008 Ellis County Press:www.elliscountypress.com

To search TTC News Archives clickHERE

To view the Trans-Texas Corridor Blog clickHERE

Demotion, removal of anti-TTC articles cause stir

April 4th, 2008

Ellis County Press

Copyright 2008

WAXAHACHIE – Residents researching the Waxahachie Daily Light website in hopes of finding articles on the Trans-Texas Corridor were recently surprised to find they had been removed.

Would this be because Macquarie Media Group, ( based out of Australia) the WDL’s new corporate owners, have strong ties with the TTC?

Some political observers and journalists believe Macquarie – whose principal partner is Spanish King Juan Carlos – is a key player in the consortium to build the North America's SuperCorridor Coalition, starting first with Gov. Rick Perry’s Trans-Texas Corridor, a network of private toll roads and high-speed highway lanes that will parallel the state’s current interstate highway system.

The same observers who reported on the media buyout of the WDL and 39 other papers – including the Ennis Journal, Italy News-Herald, Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Chronicle – believe Macquarie is silencing opposition to the TTC. Macquarie and King Carlos are investors in the TTC.

Neal White, who was demoted to editor after the buyout, told The Ellis County Press “We've been leading the state in coverage and will continue to do so.”

Jeremy Halbreich, the president of American Consolidated Media, the Dallas-based media firm Macquarie bought, said the media firm would not have a direct influence over what its member papers cover.

“No in any way, shape or form,” he said.

Having managed The Dallas Morning News for 10 years, Halbreich said he strongly respects reporters and what they do.

“ There is no interlocking directors or connections at all,” said Halbreich. “The firm is two separate companies.”

Allegations that ACM was siding with one side over the other was characterized by Halbreich “absolutely ridiculous if not insulting.”

Halbreich said his papers try to cover both points of view, but if Ellis County readers had questions, he said he would be happy to talk with them.

When The Ellis County Press called in reference to the missing TTC articles on the WDL archives, representatives of the paper said their website hosting switch in December was the cause of certain articles missing.

However, archived articles relating to various local issues were found. Articles and editorials relating to the WDL’s anti-TTC coverage were taken off.

Two different reporters for this paper conducted searches over the span of a month. When notified of this, ACM manager Jeremy Halbreich said the reporters might have been performing the searches incorrectly.

After the WDL was contacted about the situation, The Ellis County Press was able to find the once-missing archives.

“Must've been the flip of a switch,” Halbreich said. The site is now showing over 200 results from the past 744 days.

© 2008 Ellis County Press:

To search TTC News Archives click

To view the Trans-Texas Corridor Blog click

Friday, April 04, 2008

Taxpayers Beware: "Fees in the billions above normal public-private partnership (PPP) rates of return have gone to the investment banks."

Macquarie model blowtorched

'Of prurient interest is their work on fees.'

April 4, 2008

Michael West

The Sydney Morning Herald

Copyright 2008

New York-based corporate governance service RiskMetrics Group, has delivered a stinging rebuke to Australia's infrastructure sector, and in particular the "Macquarie Model" which has been mimicked by Babcock & Brown, and has spawned a generation of toll-roads, airports, telecommunications and power generation stocks. (Link: "Infrastructure Funds: Managing, Financing and Accounting; In Whose Interest?")

In the most detailed independent research of Macquarie Group and Babcock satellites to be published, Risk Metrics critiques the financially-engineered infrastructure model for its high debt levels, high fees, paying distributions out of capital rather than cashflow, overpaying for assets, related-party transactions, booking profits from revaluations, poor disclosure, myriad conflicts of interest, auditor conflicts and other poor corporate governance.

The RiskMetrics research is likely to send shockwaves through the sector and give both state and federal governments cause for concern as governments have mostly privatised public assets via these structures.

RiskMetrics is a leading adviser to institutional investors both in Australia and overseas. They have been a critic for some time of individual transactions, but this is first time they have strung all the pieces together, and raised doubts about the model's viability.

An example of RiskMetrics' previous scepticism was its advice to domestic institutions to vote against the Macquarie Bank remuneration report last year. The result was a 20% protest vote against the bank's pay structures.

Anyway, this report is a haymaker.

Although the report has not put a figure on it, fees in the billions above normal public-private partnership (PPP) rates of return have gone to the investment banks.

"The infrastructure model raises investment-related concerns that can be grouped as follows: a series of issues related to the sustainability of the model; a danger of overpaying for assets; fee structures that deliver high fees and provide an incentive to increase a fund's size; and accounting practices that have the capacity to provide an overly robust picture of a fund's profitability,'' says the report.

The model was "pioneered by Australia's Macquarie Group" and the research covers Macquarie Airports, Macquarie Capital Alliance Group, Macquarie Communications Infrastructure Group, Macquarie Media Group and the original and largest fund:

Macquarie Infrastructure Group and Babcock & Brown spinoffs Babcock & Brown Infrastructure, Babcock & Brown Capital, Babcock & Brown Environmental Investments (presently subject to a takeover offer by Babcock & Brown), Babcock & Brown Wind Partners and Babcock & Brown Power, as well as Rivercity Motorway, Duet, Hastings Diversified, Challenger, ConnectEast SP AusNet and Spark Infrastructure.

The initial success of the model, at least in capital raising and fee generation terms, has allowed the growth in infrastructure funds to expand overseas into US and European markets.

RiskMetrics, meanwhile, had been chipping away earlier at the more ambitious deals being done by Macquarie-type acolytes, such as Allco Finance Group.

For example, it recommended strongly against the Allco proposal to buy Rubicon Asset Management last year, and institutions came close to voting the deal down.

Allco principal David Coe had led an Allco roadshow to spruik the merits of the deal and it finally scraped through.

In retrospect, Allco shareholders should have taken RiskMetrics' advice. The Rubicon transaction proved disastrous.

The three Rubicon trusts are now down more than 80% in just a few months and Allco teeters on the verge of insolvency.

In the case of Allco, the proxy adviser raised doubts about corporate governance and potential conflicts of interest on the Rubicon.

It should also be noted that the adviser was a critic of MFS, Centro and ABC Learning for some of the same reasons it has criticised Babcock and Macquarie in its latest, most in-depth, paper.

Those three, like Allco and Rubicon, are close to corporate extinction.

MFS, Allco and Centro all favoured the externally-managed model as does the Hedley pubs stable of companies which has just fallen into trouble. Many real estate trusts or REITs also have the trust structure.

Their underperformance has been significant since the downturn in credit markets as the aggressive financing practices, and booking profits from revaluations, hamper performance when credit spreads blow out and asset values come under pressure.

But back to the latest RiskMetrics report. Of prurient interest is their work on fees.

As an extreme example, it takes Babcock & Brown Wind Partners which "had operating cash flow of $14.2 million in the 2006 financial year, but paid distributions totalling $48 million in relation to that year. The distributions were equivalent to 54% of the total cash receipts from customers during the year,'' says the report.

"Even the most mature infrastructure fund of all, Macquarie Infrastructure Group, is no exception.

It had operating cash flow of $306.9 million in the 2006 financial year, but paid distributions totalling $512.9 million in relation to that year.

Furthermore, the distributions were equivalent to 116% of the total toll revenue received during the year.''

The ''stapled'' entities of the infrastructure model "have multiple boards, and are run by an external management company employed under a management agreement providing for substantial fees.

Many of the features of these vehicles appear to make it practically difficult, and possibly expensive, for investors to replace the external manager if dissatisfied with its performance.''

In sum, RiskMetrics finds the model probably has more in common with private equity than with publicly traded property funds.

mwest@fairfax.com.au

© 2008 The Sydney Morning Herald:business.smh.com.au

To search TTC News Archives clickHERE

To view the Trans-Texas Corridor Blog clickHERE

'Of prurient interest is their work on fees.'

April 4, 2008

Michael West

The Sydney Morning Herald

Copyright 2008

New York-based corporate governance service RiskMetrics Group, has delivered a stinging rebuke to Australia's infrastructure sector, and in particular the "Macquarie Model" which has been mimicked by Babcock & Brown, and has spawned a generation of toll-roads, airports, telecommunications and power generation stocks. (Link: "Infrastructure Funds: Managing, Financing and Accounting; In Whose Interest?")

In the most detailed independent research of Macquarie Group and Babcock satellites to be published, Risk Metrics critiques the financially-engineered infrastructure model for its high debt levels, high fees, paying distributions out of capital rather than cashflow, overpaying for assets, related-party transactions, booking profits from revaluations, poor disclosure, myriad conflicts of interest, auditor conflicts and other poor corporate governance.

The RiskMetrics research is likely to send shockwaves through the sector and give both state and federal governments cause for concern as governments have mostly privatised public assets via these structures.

RiskMetrics is a leading adviser to institutional investors both in Australia and overseas. They have been a critic for some time of individual transactions, but this is first time they have strung all the pieces together, and raised doubts about the model's viability.

An example of RiskMetrics' previous scepticism was its advice to domestic institutions to vote against the Macquarie Bank remuneration report last year. The result was a 20% protest vote against the bank's pay structures.

Anyway, this report is a haymaker.

Although the report has not put a figure on it, fees in the billions above normal public-private partnership (PPP) rates of return have gone to the investment banks.

"The infrastructure model raises investment-related concerns that can be grouped as follows: a series of issues related to the sustainability of the model; a danger of overpaying for assets; fee structures that deliver high fees and provide an incentive to increase a fund's size; and accounting practices that have the capacity to provide an overly robust picture of a fund's profitability,'' says the report.

The model was "pioneered by Australia's Macquarie Group" and the research covers Macquarie Airports, Macquarie Capital Alliance Group, Macquarie Communications Infrastructure Group, Macquarie Media Group and the original and largest fund:

Macquarie Infrastructure Group and Babcock & Brown spinoffs Babcock & Brown Infrastructure, Babcock & Brown Capital, Babcock & Brown Environmental Investments (presently subject to a takeover offer by Babcock & Brown), Babcock & Brown Wind Partners and Babcock & Brown Power, as well as Rivercity Motorway, Duet, Hastings Diversified, Challenger, ConnectEast SP AusNet and Spark Infrastructure.

The initial success of the model, at least in capital raising and fee generation terms, has allowed the growth in infrastructure funds to expand overseas into US and European markets.

RiskMetrics, meanwhile, had been chipping away earlier at the more ambitious deals being done by Macquarie-type acolytes, such as Allco Finance Group.

For example, it recommended strongly against the Allco proposal to buy Rubicon Asset Management last year, and institutions came close to voting the deal down.

Allco principal David Coe had led an Allco roadshow to spruik the merits of the deal and it finally scraped through.

In retrospect, Allco shareholders should have taken RiskMetrics' advice. The Rubicon transaction proved disastrous.

The three Rubicon trusts are now down more than 80% in just a few months and Allco teeters on the verge of insolvency.

In the case of Allco, the proxy adviser raised doubts about corporate governance and potential conflicts of interest on the Rubicon.

It should also be noted that the adviser was a critic of MFS, Centro and ABC Learning for some of the same reasons it has criticised Babcock and Macquarie in its latest, most in-depth, paper.

Those three, like Allco and Rubicon, are close to corporate extinction.

MFS, Allco and Centro all favoured the externally-managed model as does the Hedley pubs stable of companies which has just fallen into trouble. Many real estate trusts or REITs also have the trust structure.

Their underperformance has been significant since the downturn in credit markets as the aggressive financing practices, and booking profits from revaluations, hamper performance when credit spreads blow out and asset values come under pressure.

But back to the latest RiskMetrics report. Of prurient interest is their work on fees.

As an extreme example, it takes Babcock & Brown Wind Partners which "had operating cash flow of $14.2 million in the 2006 financial year, but paid distributions totalling $48 million in relation to that year. The distributions were equivalent to 54% of the total cash receipts from customers during the year,'' says the report.

"Even the most mature infrastructure fund of all, Macquarie Infrastructure Group, is no exception.

It had operating cash flow of $306.9 million in the 2006 financial year, but paid distributions totalling $512.9 million in relation to that year.

Furthermore, the distributions were equivalent to 116% of the total toll revenue received during the year.''

The ''stapled'' entities of the infrastructure model "have multiple boards, and are run by an external management company employed under a management agreement providing for substantial fees.

Many of the features of these vehicles appear to make it practically difficult, and possibly expensive, for investors to replace the external manager if dissatisfied with its performance.''

In sum, RiskMetrics finds the model probably has more in common with private equity than with publicly traded property funds.

mwest@fairfax.com.au

© 2008 The Sydney Morning Herald:

To search TTC News Archives click

To view the Trans-Texas Corridor Blog click

TFB independent study, led by Baylor Law School Professors, examines the TTC, its implications on landowners, communities and the state of Texas

Trans-Texas Corridor:

A special report from the Texas Farm Bureau

No one issue in recent history has rallied the ranks of Texas landowners quite like the controversial Trans-Texas Corridor (TTC). Between less-than-transparent contracts negotiated with foreign firms and plans that could grab thousands of acres of the state’s most valuable farmland, mere mention of the TTC is apt to leave a sour taste in many mouths around Texas. While finding solutions to the transportation issues facing the Lone Star State will no doubt be a daunting task, one thing is certain for members of the state’s largest farm organization— action must be taken now in order to stop the wheels already in motion. Texas Farm Bureau’s board of directors recently sought an independent study to review some of the issues tied to current TTC proposals. That study, led by Baylor Law School Professors David Guinn, Michael Morrison and Matthew Cordon, examines the TTC and its implications on landowners, communities and the state of Texas as a whole. In an effort to better inform the Farm Bureau membership on the TTC issue, the editors of Texas Agriculture will present a three-part series based on that study. The first segment serves as a basic overview of the options available to Texas’ transportation problems, the second will review the historical aspects of the TTC development, and the third will explore some of problems identified within the contractual process presented thus far.

Part I

Transportation Troubles

Nobody questions that the state of Texas faces significant issues related to its highway system, which includes approximately 79,000 miles of state-owned highways. Traffic congestion plagues not only the major metropolitan areas, but also many of the less populated areas of the state.

The state’s population is expected to increase by as many as 14 million people by 2030, and a substantial percentage of this growth will take place along the route of I-35 between the Dallas/Fort Worth Metroplex and San Antonio.

Traffic congestion has continually worsened, and by some estimates, the congestion could increase by as much as 98 percent during the next 25 years if the state maintains its current funding levels for transportation infrastructure.

So how do we increase funding for these needed highway projects?

Under the current system, the state relies on three sources for the funding of normal transportation spending: (1) the state motor fuel tax, which has remained constant at 20 cents per gallon since 1992; (2) the federal motor fuel tax of 18.4 cents per gallon; and (3) motor vehicle registration fees.

Maintenance and rehabilitation costs alone account for about 85 percent of the annual spending by the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT), leaving relatively little for expansion projects.

TxDOT’s budget shortfall during the next 25 years—meaning the amount of unfunded need—has been independently estimated at $56 billion.

Funding options explored

Due to funding shortfalls and massive growth projections, the state of Texas began to investigate alternative methods for constructing and financing highways in the state.

State officials said that increasing the motor fuels tax was one option, but that the state would have to raise the tax to $1.20 per gallon in order to raise the necessary funds.

TxDOT, which has erroneously estimated its budget shortfall to be $86 billion, has stressed repeatedly how much the increase in the gas tax would have to be to cover this deficit.

Other options, such as bonded indebtedness, have been mentioned but not seriously considered as long-term solutions to the funding issues.

One idea that took hold was the use of toll roads to accelerate highway projects.

As originally conceived, tolling could be used to finance new lane expansions and for new location highways, among other uses.

In 2001, Texas began to move away from its traditional pay-as-you-go model of financing by authorizing the use of toll equity. Toll equity allows the state to use state highway funds to cover shortfalls in costs during the construction of a toll road, and these funds do not need to be repaid.

Funds could also be used for such projects as county toll roads and projects coordinated by regional tolling authorities. The original conception of the use of these toll roads was not only to allow the state to build and operate the roads at an accelerated pace compared with the use of traditional funding, but also to allow local authorities to coordinate their own projects and own their own toll roads.

Other funding options involving private entities have also been identified. One such option was the use of public-private partnerships both to fund and to operate the toll roads. In these agreements, private entities offer significant payments up front (known as concession fees) for the right to operate the toll roads and collect toll revenues for a stated period of time.

The benefit in these agreements is that the state not only sees immediate construction of new highways and new lanes on existing highways, but it also receives cash up front. These public-private partnerships have become popular in Europe and have been used in certain toll projects in the United States.

Other funding options are also available, including the following:

- Indexing of the motor fuels tax, coupled with a strategy to borrow against revenue streams; this plan is based on and supported by a study conducted by Dr. David Ellis of Texas A&M, a member of the Governor’s Business Council;

- Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) credit program;

- Section 129 loans, which provide federal funding for toll facilities that are not part of the Interstate Highway System;

- Specially secured debt instruments;

- Texas Mobility Fund;

- State infrastructure banks; and

- Tax increment financing, based on projections for property values.

The legislation in 2001 authorized the use of toll equity, meaning that the state could invest highway funds into the toll roads. And in 2002, Gov. Rick Perry and TxDOT announced plans detailing what would become an extremely controversial 4,000-mile highway system.

TTC unveiled

The Trans-Texas Corridor, as laid out in Gov. Perry’s plan, would consist of new roadways that would parallel I-35, I-37, I-45, I-10, and the proposed I-69.

The new highways would have rights-of-way as wide as 1,200 feet in some locations, would have separate lanes for automobiles and trucks, would have high-speed passenger and freight rail, and would have a dedicated utility zone.

TxDOT estimated the costs for the entire corridor at between $145.2 billion and $183.5 billion. A significant piece of legislation passed in 2003, H.B. 3588, officially authorized the creation of the TTC and broadened the authority given to TxDOT to finance the project.

TxDOT moved ahead with the planning phases of the TTC, focusing its attention primarily on the 560-mile TTC-35, which would run from the Texas-Oklahoma border to Mexico. The near-term focus has been on a 332-mile stretch from the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex to San Antonio.

Plans for this highway would run the 1,200-foot wide corridor on a route roughly parallel to and to the east of I-35.

According to estimates based on current plans, construction of the near-term facilities would require the acquisition of 71,661 acres, as well as a total of 8,036.5 parcels of land. The total aggregate estimate for these right of way costs alone was $1.62 billion.

In December 2004, the Texas Farm Bureau convention delegates adopted a policy that opposed the TTC. For two years prior to that time, Farm Bureau’s leadership worked to develop policy concerning the planned toll way, and during this period, several groups throughout the state were not fully aware of the extent of the negative consequences pertaining to the TTC.

Thus, the bills passed in 2001 and 2003 met far less opposition than the legislation introduced in 2005 and 2007. Since 2005, the Texas Farm Bureau has actively and openly opposed the Trans-Texas Corridor.

In 2005, TxDOT entered into a Comprehensive Development Agreement (CDA) with Cintra Zachry L.P., a consortium led by the Spanish firm of Cintra Concesiones de Infraestructuras de Transporte, S.A., along with Zachry Construction Corporation of San Antonio.

While this agreement does not authorize the construction of any segment of TTC-35, it serves as the guide for the execution of a series of segment development contracts.

To date, the only segment agreement that has been executed applies to two segments of SH-130, which will be examined in detail in the final part of this series.

Subsequent issuance of a Master Development Plan (MDP) by Cintra Zachry detailed the development of each segment of TTC-35, and paved the way for TxDOT and the Federal Highway Administration to begin the process of an environmental impact study under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

It is important to note that until the NEPA processes are complete, no further planning of the proposed toll way routes can occur. The length of the NEPA process varies, taking as long as three to four years to complete.

Controversial corridor

Planning of the TTC has given rise to a growing number of concerns, many of which directly affect the agricultural interests that the Texas Farm Bureau represents.

Most notably, the corridor will require the acquisition of thousands of acres of land through purchase and through the exercise of the state’s power of eminent domain.

The concern regarding the use the power of eminent domain and the interest in protection of property owners led to the proposal of H.B. 2006 during the 80th Legislature in 2007.

This bill would have provided protections for property owners by requiring that public entities follow certain procedures to acquire property through eminent domain and by establishing provisions that would ensure that property owners receive fair market value for their land.

Gov. Perry vetoed this bill after it passed in both the House and Senate, citing concerns that the bill would "enrich a finite number of condemnation lawyers."

Even prior to the introduction of H.B. 2006, opposition toward the TTC was mounting regarding agreements struck between TxDOT and Cintra Zachry.

Most notably, the concession fee agreement as laid forth in initial contracts would severely restrict the ability of TxDOT to build or renovate roadways that would compete with the toll way.

In fact, the agreement forces TxDOT either to lower the speed limit on I-35 in order to divert traffic to the toll way for the purpose of raising toll revenues for Cintra Zachry or to pay damages for any lost toll revenue.

The likely result of the toll way system under a collection of these types of these agreements would mean that, as Sen. John Carona put it, "Within 30 years’ time, under existing comprehensive development agreements, we’ll bring free roads in this state to a condition of ruin."

This opposition led to the enactment of S.B. 792 in 2007, which established a two-year moratorium on the execution of agreements such as the one that applies to SH-130.

This moratorium expires on Aug. 31, 2009.

For the Texas Farm Bureau to be effective in its opposition to the TTC, it must act during this time frame before TxDOT is able to enter into more agreements.

Part II

Creating the monster

Creating the monster

No one issue in recent history has rallied the ranks of Texas landowners quite like the controversial Trans-Texas Corridor (TTC). But long before the nightmare even had a name, several key pieces of legislation were introduced and passed, paving the way for what some call the biggest Texas land grab in history. Texas Farm Bureau’s board of directors recently sought an independent study to review some of the issues tied to current TTC proposals. That study, led by Baylor Law School Professors David Guinn, Michael Morrison and Matthew Cordon, examines the TTC and its implications on landowners, communities and the state of Texas as a whole. In an effort to better inform the Farm Bureau membership on the TTC issue, the editors of Texas Agriculture are presenting a three-part series based on the Guinn study. This segment will review the historical aspects of its development. The final installment will explore some of problems identified within the contractual processes as presented thus far.

Long before lawmakers and landowners began cussing and discussing the super highway called the TTC, a number of state laws were passed to pave its way.

So what exactly took place to allow the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) to authorize agreements with Cintra Zachry, a consortium led by the Spanish firm of Cintra Concesiones de Infraestructuras de Transporte, S.A., along with Zachry Construction Corporation of San Antonio, that would take control of the TTC under current plans?

To answer that, one must look back to actions of the State Legislature beginning in 2001, many of which sailed through the Austin lawmaking process with little or no fanfare. They included:

- S.B. 342 (2001)—Prior to this bill’s enactment during the 77th Legislature, TxDOT could expend funds for toll projects, but only if these funds were repaid from the revenues produced by the tolls. TxDOT could not advance funds for a turnpike or toll development project without an obligation of repayment.

- Now, public entities are no longer required to repay funds expended for toll projects, and TxDOT is authorized to expend funds for the cost of toll projects of both public and private entities.

- S.J.R. 16 (2001)—Joint Resolution 16, or Proposition 15, created the Texas Mobility Fund, a revolving fund that is part of the state treasury and is administered by the Texas Transportation Commission.

- H.B. 3588 (2003)—Passed during the 78th Legislature, this bill is the most significant piece of legislation related to the TTC. In fact, many of its provisions are now contained in Chapter 227 of the Texas Transportation Code.

Despite the fact that this bill made such monumental changes to the State’s approach to highway construction, operation, and financing, few members of the Legislature apparently were aware of the contents of the bill. As a result, TxDOT is authorized to collect money from private entities with little legislative oversight.

The concession fees are authorized to be paid directly to TxDOT and not to the state treasury, although the funds may still be audited.

The State Auditor’s Office in 2007 recommended that funds generated by toll revenues should be deposited into the state highway fund and be subject to legislative appropriation. TxDOT responded that these revenues were "already subject to appropriation" but did not address the fact that the revenues were not subject to legislative appropriation.

- H.B. 2702 (2005)—After the enactment of H.B. 3588, members of the legislature became aware of some problems with the legislation.

This bill also restricts the ability of TxDOT to acquire land for purposes other than the traffic lanes, rail lines, utility corridors, and equipment storage. It also requires TxDOT to use the land it condemns within 10 years of its condemnation, or else the land reverts back to the original owner.

Texas Farm Bureau Associate Legislative Director Warren Mayberry spoke against H.B. 2702 at the House hearings, saying it could have negative effects on property rights because it authorizes TxDOT to lease condemned land to private business interests. Moreover, property owners expressed concerns that the placement of the TTC will severely limit access to property that is bisected by the corridor.

Some of these concerns were caused by H.B. 2702, including the provision that allows TxDOT to lease the land for business purposes. Other complaints were raised because H.B. 2702 failed to address concerns that had been previously raised, such as the problem with a landowner’s access to his property.

Monster is born

The lawmaking process described above allowed TxDOT to proceed with its planning of TTC, including execution of the agreements with Cintra Zachry.

In the time since, a number of voluminous documents, including contracts and conceptual plans, were produced along the way.

But collection of all of these documents has proven to be a challenge. In fact, a report issued by the State Auditor’s Office in February 2007 regarding the TTC and TxDOT suggested that TxDOT had failed to make all documentation available to the public in a timely manner.

Yet regardless of opinions regarding the release on information, one fact was certain by the time of the auditor’s report: The TTC was already well underway, with or without public knowledge.

One year after voters approved Proposition 15, TxDOT released a report summary in June 2002 entitled Crossroads of the Americas: Trans-Texas Corridor Plan. This report focused on the entire 4,000-mile corridor, which would include the following facilities:

- I-35, running from the Texas-Oklahoma border to the Mexican border;

- I-37, running from San Antonio to Corpus Christi;

- A corridor that would run from Denison to the Rio Grande Valley (part of the proposed I-69);

- A corridor that would run from Texarkana to Laredo through Houston (another part of I-69);

- I-45, running from Dallas-Fort Worth to Houston; and

- I-10, running from El Paso to Orange.

Accordingly, TxDOT’s estimates in 2002 indicated that the entire TTC would cost between $145.2 billion and $183.5 billion.

On Dec. 16, 2004, the Texas Transportation Commission announced that it had selected Cintra Zachry to develop TTC-35. That company proposed at that time to invest $6 billion to construct the portion running from D/FW to San Antonio, along with another $1.2 billion for additional improvements. According to this proposal, the initial segment would be completed by 2010.

Following that agreement, TxDOT signed a Comprehensive Development Agreement (CDA) with Cintra Zachry on March 11, 2005.

That CDA was basically an umbrella agreement for individual projects related to TTC-35. It generally allowed for the developer to design, develop, construct, finance, acquire, operate and/or maintain roadway facilities.

It is used as an alternative to low-bid procurement and pay-as-you-go funding.

According to the Guinn report, the CDA for TTC-35 does not contain the key contractual information for the overall construction of the corridor. Rather, the specific information is contained in individual facility, or segment, agreements, such as the SH-130 agreement, which will be examined in detail in the final part of this series.

The auditor’s report released in February 2007 noted that the SH-130 contract and the CDA were significantly different, and "these differences show the inherent limitations of Comprehensive Development Agreement contracts in providing detailed business terms."

As part of the requirements under National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA), TxDOT and the Federal Highway Administration on April 4, 2006, submitted a six-volume Tier One Environmental Impact Statement to the Environmental Protection Agency.

The purpose of this report is to select the preferred alternative for the specific route for TTC-35. Until the NEPA process is complete, TxDOT cannot proceed with further planning regarding the route.

Approval of a route is outside of the control of TxDOT and is one of the events that has slowed further development of the TTC up to this point.

The CDA already in place required Cintra Zachry to create both a master development plan and a master financial plan. That master plan was released on Sept. 28, 2006, although some elements still may be developed later in time.

It clarified a number of aspects of the operational, administrative, and financial structure of TTC-35, though the financial assumptions in the document are generally only estimates.

Still, those estimates offered some valuable insights to those concerned about the TTC. For example, the projected cost of a one-way trip from Dallas to Austin (164 miles) on TTC-35 would be $20.50 according to the MDP, assuming that the toll rate of $0.125 per mile for an automobile applies as expected. The cost for a truck traveling the same distance would be $78.72.

Even more disturbing than the costs of using the TTC, however, came in the facility concession agreement struck between TxDOT and Cintra Zachry on March 22, 2007, for the development of SH-130.

Although this agreement is not part of TTC-35, the contract offers insight about how future segment agreements may be drafted, the Guinn report says. In fact, many of the complaints about specific aspects of the TTC have been raised because of terms found in the SH-130 contract.

The two most problematic areas of this contract include the inclusion of a non-compete clause in the agreement, and the lack of a provision that allows TxDOT to purchase Cintra Zachry’s interest in the contract at a price that is fair for taxpayers.

While most attention had focused on TTC-35, TxDOT had another monster waiting in the wings for Texas landowners, and in November 2007, the agency submitted a Tier One Draft Environmental Impact Statement for TTC-69, marking the first step for the development of Interstate 69 as well as elements of the Trans- Texas Corridor.

The proposed roadway would extend from Texarkana to Laredo and would pass through Marshall, Lufkin, Huntsville, Houston, Wharton, and Corpus Christi.

The project is probably several years behind TTC-35 in development, though, due to the fact that most segments of this roadway could not generate enough toll revenues to make it profitable.

Taking the monster down

Given the likelihood of increased condemnations with the building of TTC, the Texas Legislature passed H.B. 2006 in 2007, which would have protected landowners through a variety of means.

It would have modified the processes governing eminent domain proceedings, the standards of evidence that a court could consider when making decisions regarding damages, the obligations placed upon condemning entities, and the rights of previous owners to repurchase condemned property.

The bill would have allowed special commissioners to consider evidence of factors that would be considered in a transaction between private buyers, thus giving landowners a greater chance to receive fair market value for their property.

It also allowed property owners to recover damages when a condemnation would result in diminished access to the landowner’s remaining property.

Another provision, known as the "Truth in Condemnation Procedures Act," would have required greater transparency by the government when it initiated a condemnation proceeding. This part of the bill would have required the government to make a good faith effort to acquire private property through voluntary purchase or lease.

If the governmental entity had failed to make such a good faith effort under this bill, a court could require the condemning entity to pay all costs and reasonable attorney’s fees incurred by the property owner.

Gov. Rick Perry ultimately crushed those protections with his veto pen because of the cost to the state.

Perry also stated that he opposed the bill due to "11th hour" changes. That proved less than accurate, the Guinn report says. The specific provisions Perry cites in support of the claim were contained in committee substitutes introduced in March 2007, more than two months prior to the end of the legislative session.

Perry’s final reason for nixing the eminent domain reform bill came in concerns about the enrichment of condemnation lawyers, who he said would get rich at the expense of state tax dollars.

According to the Guinn report, that logic disregards the fact that the bill probably would have prevented litigation because the provisions allowed landowners to negotiate a fair price for their property.

Concerns about the terms contained in the SH-130 contract, along with the veto of H.B. 2006 by Gov. Perry, led the Legislature to pass S.B. 792, preventing TxDOT from entering into a comprehensive development agreement after May 1, 2007.

As the Guinn report points out, that fix is only temporary. The moratorium on such agreements expires on Aug. 31, 2009.

While lawmakers attempted to stop the monster called TTC, TxDOT has worked actively to keep the beast alive. In fact, recent actions by TxDOT show that it will practically stop at nothing to fight for this toll system, the Guinn report says.

Facing mounting opposition to the TTC, TxDOT in August 2007 initiated an advertising campaign designed to promote the TTC and the use of toll roads.

The total cost of the campaign has been estimated to be between $7 million to $9 million and includes billboard as well as radio advertising.

The department defended the campaign by saying that it was using the advertising as a means of "engaging the public." Members of the legislature, including Warren Chisum and Lois Kolkhorst, said that this was nothing more than a waste of taxpayer money.

TxDOT also has tried to "repurchase" interstate highways from federal government. Because federal law prohibits states from tolling roadways that have already been constructed with federal money, TxDOT has sought to repay the federal government for the funds used so that the department could then convert the highways into toll roads.

In a report entitled Forward Momentum, submitted in February 2007, TxDOT urged Congress to "allow states to ‘buy back’ or reimburse the federal government for its share of investment in interstate segments."

This plan likely would involve a tolling agreement similar to the TTC, meaning that the state would enter into a long-term deal with a private entity to allow the private entity to collect the toll revenues.

U.S. Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison has argued against tolling the existing interstate highways and introduced legislation in 2007 that would prevent TxDOT from moving forward with its plan.

Her action, too, is only a temporary fix, the Guinn report says.

Sen. Hutchison’s amendment only provides for a one-year moratorium against the approval of tolls on these highways.

Given other agency actions in recent years, State Sen. John Carona and others have expressed concerns that TxDOT will attempt to circumvent the moratorium established in S.B. 792.

While preventing TxDOT from entering into comprehensive development agreements with private entities, it is not clear whether it covers other types of agreements.

It is possible, they believe, that TxDOT could try to enter into a so-called "availability agreement" with Cintra or another entity and argue that this agreement is merely an extension of the existing CDA. These availability agreements relate to fund-raising groups and are classified as research-related instead of funding for projects.

Part III

Who benefits most?

Who benefits most?

No one issue in recent history has rallied the ranks of Texas landowners quite like the controversial Trans-Texas Corridor (TTC). Yet beyond unresolved transportation issues, beyond costly tolls charged to travelers coursing our state, and beyond the massive land grab needed to see the 4,000-mile super highway to fruition, lies a questionable contract with a foreign firm that raises the ire of both rural and urban Texans alike. Texas Farm Bureau’s board of directors recently sought an independent study to review some of the issues tied to current TTC proposals. That study, led by Baylor Law School Professors David Guinn, Michael Morrison and Matthew Cordon, examines the TTC and its implications on landowners, communities and the state of Texas as a whole. In an effort to better inform the Farm Bureau membership on the TTC issue, the editors of Texas Agriculture are presenting a three-part series based on the Guinn report. This final installment explores some of problems identified within the contractual processes as presented thus far.

The Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) has been, to say the least, less than transparent with regard to its presentation of contracts and financial information pertinent to the many projects tied to the TTC.

Like most contractual matters, the devil is somewhere in the details, and the details uncovered so far have raised some deep concerns, according to the Guinn report.

Most notably, the report said, one question remains unanswered in relation to these dealings: Who will wind up benefiting most, the Texas taxpayers or the foreign developer?

The concept of toll equity allows the state to expend highway funds for toll projects without requiring reimbursement. Toll equity applies not only to toll projects constructed by government entities, but also by private companies through public-and-private partnerships.

The contracts TxDOT is negotiating with Cintra Zachry (a consortium led by the Spain-based Cintra Consesiones de Infraestructuras de Transporte, S.A. and Zachry Construction Corp. of San Antonio) call for the private developer to pay a fee up front in exchange for the right to construct and operate the toll road, including the right to collect toll revenues for as long as 50 years.

This arrangement indeed solves some of the state’s short-term problems related to highways. More specifically, the report noted, a private entity takes responsibility for financing and constructing a highway project, while the state receives money up front that can be used to pay for other projects.

But that contract may not be all it’s cracked up to be, the Guinn report said.

Banks and other private firms have been lured to invest in public infrastructure due in large part to the steady cash flow that can stem from toll projects.

This cash flow is steady because of the practical monopoly that the private firms will have in operating a toll road. The toll agreements ensure a high return with virtually no monetary risk on the part of the firms who will operate the tolls.

To increase revenue, these firms can raise toll rates without adverse repercussions by voters. As the report noted, these firms stand to gain stock market-like returns for investments that are as safe as high-grade bonds.

A recent article in Business Week described the private toll equity investments as such: "Many investors think of infrastructure investing as a natural extension of the private equity model, which is based on rich cash flows and lots of debt. But there are important differences. Private equity deals typically play out over 5 to 10 years; infrastructure deals run for decades.

"And the risk levels are vastly different," the article continued. "Infrastructure is ultra-low-risk because competition is limited by a host of forces that make it difficult to build, say, a rival toll road. With captive customers, the cash flows are virtually guaranteed. The only major variables are the initial prices paid, the amount of debt used for financing, and the pace and magnitude of toll hikes—easy things for Wall Street to model."

Further, the Guinn report added, the public has received some potentially misleading information about the benefits of toll roads in Texas.

A Dallas Morning News editorial on Jan. 18, 2008, for instance, referred to a $3.2 billion concession fee paid by the North Texas Tollway Authority as a "windfall" for the Dallas-Fort Worth area. In fact, however, motorists collectively will pay far more than this amount for use of the toll road, which will exist perpetually in all likelihood rather than for the duration of time it takes to pay for the road itself.

If a private company, such as Cintra Zachry, were to be awarded a contract for TTC, the state would receive a significant amount of cash, but the citizens who use the toll road would more than repay this amount to the company through payment of steadily increasing toll rates, the Guinn report said.

Dollars and cents

An analysis of the TTC-35 plans by the State Auditor’s Office concluded that the TTC-35 project alone could cost more than $105.6 billion, according to a review of the Master Development Plan (MDP) released in 2006.

Keep in mind, TxDOT estimated costs at between $145.2 billion and $183.5 billion for the entire TTC project, which would have included new roadways along I-35, I-37, I-45, I-10 and the proposed I-69.

The MDP states that costs for design, rights-of-way, construction, operations, maintenance and financing will be borne by the developer, but the state clearly will pay some of these costs. In fact, the Guinn report noted, TxDOT was required to pay $3.5 million for the production of the MDP itself.

Moreover, the state also may pay an estimated $563.3 million for the construction of two of the facilities that are part of TTC-35. The extent to which the state may have to pay part of the costs for the entire TTC project is subject to question, the Guinn report said, because TxDOT has not provided reliable information regarding these costs.

According to the State Auditor’s Office, "auditors made an effort to sum the elements of costs, operating expenses, revenue and developer income contained within the TTC-35 MDP. Upon its review of the sums, the department stated that this financial information was not correct because it is not possible to accurately estimate profits due to many unforeseen variables.

The Guinn report also flagged several concerns raised in the auditor’s report regarding the contract between TxDOT and Cintra:

- TxDOT will be responsible for paying Cintra should a "compensation event" occur.

One of these events is a "discriminatory change in law," meaning a change that is "principally directed at and the effect of which is principally borne by" the developer or other private toll operators in the state. Another compensation event includes the operation of a facility that competes with the tollway.

- Under the contract, TxDOT will make decisions regarding speed limits based on financial considerations rather than public safety.

By contrast, TxDOT will be required to pay damages to Cintra should speed limits be changed in a manner that adversely affects the toll road. So if TxDOT increases the maximum daytime speed limit of the segment of I-35 that runs parallel to the toll road, then the state must pay Cintra for toll revenues lost as a result of that change. Likewise, if TxDOT reduces the speed limit on the toll road to less than 80 mph, then the department will have to return concession payments paid.

- TxDOT is required to provide all toll collection and enforcement services, as well as cover any lost toll payments resulting from riders who use the toll road without paying.

According to the State Auditor’s Office report, "weaknesses in the department’s accounting for project costs and monitoring of the developer create risks that the public will not know how much the state pays for TTC-35 or whether those costs were appropriate. Not adequately monitoring developers also exposes the state to future financial liability."

- TxDOT would have no control over toll rates charged by Cintra.

In the contract between TxDOT and Cintra Zachry for SH-130 Segments 5 and 6 in Austin, the contract specifies that the rates begin at $0.125 for automobiles and increase based on the sizes of the vehicles. The contract also allows Cintra Zachry to increase the toll rates "any time or times" within the maximum toll rate, which is calculated through a formula provided in the contract.

The problem, however, is that the certainty of these toll increases does not equate to certainty in service quality, the Guinn report noted. The private entities are practically guaranteed to make profits through these toll increases, meaning that they have no incentive to provide better service.

The SH-130 contract does not limit the rate of return that Cintra Zachry can receive on its equity, but the Master Development Plan refers to a "12 percent guaranteed return on equity."

TxDOT claims that this amount was used as a financial modeling assumption, yet the fact that this amount was specifically included into the MDP language demonstrates that Cintra anticipates a return greater than what one would expect to be a fair rate of return.

So what would this mean in dollars and cents to the average citizen?

The Guinn report suggested one consider the following: The Governor’s Business Council, which advises the governor on a variety of matters, concluded in 2006 that TxDOT’s $56 billion shortfall could be funded by adjusting the fuel tax rate by a rate equal to the increase in the Highway Cost Index (HCI), which would result in an average annual increase of 3.06 percent.

Under that proposal, the fuel tax would increase to $0.66 per gallon by 2030, costing the average commuter about $21 more per month. The amount spent on tolls by the same commuter, however, would likely be more than $100.

Other contractual concerns

Given the length of the public-private toll road agreements and the enormous amount of money involved in these agreements, it is important that these contractual arrangements are advantageous to Texas taxpayers.

A review of these contracts, however, shows that the developer stands to gain more than the state does with regard to these deals.

The Guinn report noted the following:

- Non-Compete Clauses—Although the SH-130 contract between TxDOT and Cintra Zachry was not originally supposed to contain a non-compete clause, it did indeed include a non-compete clause designed to protect the developer’s interests.

So if TxDOT decides to construct or expand a highway within the competing facility zone, TxDOT must pay the amount of toll revenues that Cintra Zachry will lose as a result of the competing roadway.

TxDOT can mitigate its damages by taking certain actions, including a reduction in speed limit on I-35 that has the effect of increasing revenues on the SH-130 tollway. Thus, although the contract excludes I-35 as a competing facility, the contract gives TxDOT the incentive to make I-35 less desirable as a roadway by reducing the speed limit.

TxDOT has denied that the contractual provisions related to compensation for competing facilities amount to non-compete clauses, yet the department has provided no explanation as to why these provisions were added after the original drafts did not contain any provisions regarding competing facilities.

State Sen. Robert Nichols (R-Jacksonville) explained the effect of this clause as follows: "Imagine if you could make a deal with the state to build a store in your hometown, use the state’s power of eminent domain to take the land needed for your store, and then get the state to agree to refrain from building another store in your hometown for 50 years.

"Now imagine your hometown was projected to have double-digit population growth," Nichols continued. "While it may be hard to fault any business for pursing such a deal, the taxpayers would hold elected officials accountable."

- "Buy-Back" Provisions—This type of provision is a mechanism that allows the state to purchase the interest of a private entity in a toll project during the term of the contract. It is absent from current agreements signed between TxDOT and Cintra.

"In the event the state needs to ‘buy back’ the road during the 50-year period, it is imperative for us to have a clear buy-back provision to protect taxpayers," he added. "The private companies prefer to put off addressing the buy-back issue until another day… (but) it does not take a genius to figure out the companies will calculate the price in a way that enriches shareholders and leaves taxpayers holding the bag."

The SH-130 contract does allow TxDOT to terminate the contract "for convenience," but should the department do so, Cintra is entitled to receive several types of compensation, which includes, among other items, fair market value for any and all structures existing at the time of contract termination.

As the Guinn report noted, "it is not difficult to imagine that requiring TxDOT to pay the fair market value of this interest could make termination of the contract difficult or impossible from a financial perspective."

Other contractual problems identified by the State Auditor’s Office included:

- The state did not adequately monitor whether Cintra Zachry was meeting its insurance requirements; whether Cintra Zachry’s financial stability was enough to incur the debt described in the Master Development Plan; and whether the key financial assumptions contained in the MDP, including inflation and interest rates, would be reasonable for the timeframe described.

- TxDOT had not finalized internal policies and procedures for accepting, reviewing, analyzing and processing unsolicited proposals.

- TxDOT destroyed specific documents that were prepared during the contract selection process for the Comprehensive Development Agreement. The audit concluded that "not retaining the individual scoring sheets of each committee member can lead to an appearance of impropriety in the selection process."

- The auditor’s report suggested greater Legislative oversight over the TTC project and noted that the TxDOT should "increase the transparency of the development of the Trans-Texas Corridor by increasing the public’s timely access to information."

© 2008, Texas Farm Bureau www.txfb.org

To search TTC News Archives click

To view the Trans-Texas Corridor Blog click

Thursday, April 03, 2008

"Wow, what an embarrassment."

Community Profile: Bob Daigh, TxDOT Austin District Engineer

Community Impact Newspaper

Copyright 2008

Q. What is one thing you would like people to know about TxDOT?

A. Most people don’t realize that the Austin district of TxDOT oversees the federal and state transportation system for 11 counties. The Austin district does that through the tireless efforts of about 639 dedicated, hardworking folks who are working every day to improve the safety and mobility for the citizens of Central Texas. Those are the people who are out there during the ice storms, trying to make it so the ambulance can get to the hospital. Those are the people, when everyone else is at home watching TV, who are out there in the middle of the flood, trying to block off the state road so that no one gets out there and drowns. Many times, they put their lives at risk for the benefit of Central Texas. I think that’s something that most people don’t understand.

Q. What are your responsibilities as the Austin Distict Engineer at TxDOT?

A. My primary duties are to implement the policies of the [Texas] Transportation Commission and the TxDOT administration. I manage the workforce of the Austin district [of TxDOT] and carry out those policies. I also work with the communities’ elected officials to try to ensure they understand the policies. I try to develop a work program, which promotes congestion relief, improves safety and continues to maintain our roads the best we’re able to, given the meager funding that we have.

Q. What projects are you most proud of?

A. There are different projects for different reasons. The Central Texas Turnpike project, which is the largest highway-only construction project that is bond financed in the country, and one of the largest in the world – to have been involved with that is obviously a source of pride.

[In 2003 to 2004,] the Cabela’s work that we did on [IH] 35 and our partnership with the City of Buda and Hays County to help bring Cabela’s to Hays County has a little bit of special meaning to me because that was the first business development type of activity or project that I was involved with. It was not only business, it was safety. It was the first project during my tenure that the department stepped forward to engage the local elected officials and assisted them in securing some economic development that they were badly wanting. What made that project special to me was that the mayor of Buda had negotiated certain tax breaks for Cabela’s but he had not abated the school tax, so I knew that if Cabela’s would come to the area, that there would be a significant revenue stream created for the schools in the area, and portions of Hays County were principally rooftops at that time, similar to the situation that Pflugerville has historically been in. There are small details like that most people aren’t aware of.

Q. What is the Central Texas Turnpike System?

A. The offering statement, which was used to secure financing, included the northern extension of Loop 1 from FM 734 (Parmer Lane) up to SH 45, it was SH 45 from essentially [US] 183 over to [Toll] 130, and it was SH 130 from IH 35 north of Georgetown down to [US] 183. Those three elements were all financed together in one package through bonds sold on Wall Street. That was the largest highway-owned project.

At the time, it was the biggest bond sale the state had ever done at about $2.2 billion. It was also the first toll project that really the state had undertaken in modern times.

Q. How was the Central Texas Turnpike project financed?

A. When we financed the Central Texas turnpike project, the goal was to absolutely maximize the amount of pavement that we could get on the ground. We stretched the financing to the limit. To do that, what the department did was what’s generally called backstopping, which means we would subsidize the Operations and Maintenance (O&M) expenses for the project until the traffic was high enough to collect enough revenues to where O&M support would no longer be required.

In this financing, the period of O&M support was anticipated to be well in the 20-plus year range, so that if you get traffic that is higher than projected, that means you’re getting more money than you projected. But what that extra money is first doing is lowering the amount of support you’re receiving from TxDOT. That’s not how most roads are financed. That’s not how 183A [Toll] was financed, and that’s not how we’re going to finance any of the other toll roads going forward. This was a very unusual financing because the state felt it was in their interest to maximize the pavement on the ground to make the connections that we’re making.

Q. How is the Central Texas Turnpike System different?

A. This was a 100 percent TxDOT deal, that’s what’s different. When we did this deal, there were three requirements that we had in the bond indenture. One was that we do some interchange improvements to [US] 183 and [Toll] 45.The next requirement was that unless we can’t do it environmentally, we need to construct 183A [Toll]. The third requirement was unless we can’t do it environmentally, we construct [Toll] 45 southeast.

So the 183A [Toll} project was basically set aside for the Central Texas Regional Mobility Authority as their first project. That was a starter kit for the CTRMA. It was environmentally cleared by TxDOT, the counties got together and formed the CTRMA, and so [the 183A Toll project] was given to them and TxDOT delivered the seed money.

Q. How is toll road construction traditionally financed?

A. Very few projects, if any in the entire world, can be financed totally in a traditional manner selling bonds. That means that you are able to, just from the traffic using the road, go to Wall Street and convince them that you would have enough traffic volume that would be willing to pay a high enough price to allow you to go Wall Street and borrow enough money to build the project. Generally, there is always going to need to be some cash involved. So the amount of cash participation may need to be 75 percent or 50 percent or 20 percent. It will vary for each project. Likewise the percent of bond financing will vary. Obviously if you have a project and if you finance that project you’ve got to pay just like the rent on your house or your house bill, you’ve got to pay the banker. You’ve borrowed money and so you’ve got to pay the banker or they get kind of mad at you.

Borrowing money from Wall Street is no different. You have a payment to make for the debt. But what you also have is you have to pay for the operations and you have to pay for the maintenance. Under normal financing what you do is the first dollar you get goes towards operations and maintenance and until you pay for operations and maintenance, a dollar doesn’t work its way to be available to pay for the debt service. And that’s how the bond holders generally like it because even if they don’t get paid, they want that road running and well-maintained or their asset will depreciate and that hurts their ability to ever get money.

Q. How does TxDOT prioritize which projects to do next?

A. That is really the decision of Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization. CAMPO is a federally mandated and created entity. Their principle role is to develop a coordinated multi-modal transportation plan for the region. That’s their charge. And they must develop and approve the list of projects that will go to construction. That list has to include all projects that receive a federal dollar, any federal monies, or are deemed to be regionally significant.

Q. How did TxDOT miscalculate $1.1 billion?

A. We blew it. You have to understand it isn’t one thing. It is the perfect storm of events. TxDOT has experienced, principally because of the rise in oil prices, tremendous inflation. That’s no secret. Everything we do takes large equipment. We’re using huge amounts of diesel. We have a very energy intensive construction process. There has been 100 percent inflation in the last few years. Without question, that’s part of it.

We also have an aging system. The interstate system is 50 years old. The FM and RM system is maybe 40 years old. Roads are like the roof of your house. Over time, you get a little leak, so you put on another layer of shingles. Then time goes by and you go and put up another layer of shingles. But you get to a point, after you get that second or third layer of shingles on, you have to go and scrape off all the shingles, and replace some plywood, and you put on a new roof from scratch. Roads are like that. We can continue to do surface treatments, and band-aid them and hold them together, but there gets to be a point in time when you have to just rehabilitate the road. You gotta scrape it all up and put it all down. We are facing an enormous maintenance liability. The design life of a pavement is generally in the 20 or 30 year range. These roads, many of them, are all approaching that life span, especially with the accelerated roads and traffic that we’re seeing.

You have all of this and you have some miscalculations, or over-projections of federal dollars that are going to come in. We have increasing costs and increasing need, and now we’ve over-projected how much federal revenue is going to come in. We didn’t curtail our spending fast enough. That’s just how it is. It’s ugly, it’s embarrassing, but that’s just how it is.

Given all of this backdrop, which is enough, I mean that is crashing the bus into the wall as it is, but we accelerate the crashing of the bus with an unfortunate, honest mistake, where evidently, monies were allocated to pay for both some projects that have been let [already started], and also simultaneously allocated for some future builds. Wow, what an embarrassment. And it took a long time to find it.

© 2008,Community Impact Newspaper:www.impactnewspaper.com

To search TTC News Archives clickHERE

To view the Trans-Texas Corridor Blog clickHERE

Community Impact Newspaper

Copyright 2008

Q. What is one thing you would like people to know about TxDOT?

A. Most people don’t realize that the Austin district of TxDOT oversees the federal and state transportation system for 11 counties. The Austin district does that through the tireless efforts of about 639 dedicated, hardworking folks who are working every day to improve the safety and mobility for the citizens of Central Texas. Those are the people who are out there during the ice storms, trying to make it so the ambulance can get to the hospital. Those are the people, when everyone else is at home watching TV, who are out there in the middle of the flood, trying to block off the state road so that no one gets out there and drowns. Many times, they put their lives at risk for the benefit of Central Texas. I think that’s something that most people don’t understand.

Q. What are your responsibilities as the Austin Distict Engineer at TxDOT?

A. My primary duties are to implement the policies of the [Texas] Transportation Commission and the TxDOT administration. I manage the workforce of the Austin district [of TxDOT] and carry out those policies. I also work with the communities’ elected officials to try to ensure they understand the policies. I try to develop a work program, which promotes congestion relief, improves safety and continues to maintain our roads the best we’re able to, given the meager funding that we have.

Q. What projects are you most proud of?

A. There are different projects for different reasons. The Central Texas Turnpike project, which is the largest highway-only construction project that is bond financed in the country, and one of the largest in the world – to have been involved with that is obviously a source of pride.

[In 2003 to 2004,] the Cabela’s work that we did on [IH] 35 and our partnership with the City of Buda and Hays County to help bring Cabela’s to Hays County has a little bit of special meaning to me because that was the first business development type of activity or project that I was involved with. It was not only business, it was safety. It was the first project during my tenure that the department stepped forward to engage the local elected officials and assisted them in securing some economic development that they were badly wanting. What made that project special to me was that the mayor of Buda had negotiated certain tax breaks for Cabela’s but he had not abated the school tax, so I knew that if Cabela’s would come to the area, that there would be a significant revenue stream created for the schools in the area, and portions of Hays County were principally rooftops at that time, similar to the situation that Pflugerville has historically been in. There are small details like that most people aren’t aware of.

Q. What is the Central Texas Turnpike System?

A. The offering statement, which was used to secure financing, included the northern extension of Loop 1 from FM 734 (Parmer Lane) up to SH 45, it was SH 45 from essentially [US] 183 over to [Toll] 130, and it was SH 130 from IH 35 north of Georgetown down to [US] 183. Those three elements were all financed together in one package through bonds sold on Wall Street. That was the largest highway-owned project.

At the time, it was the biggest bond sale the state had ever done at about $2.2 billion. It was also the first toll project that really the state had undertaken in modern times.

Q. How was the Central Texas Turnpike project financed?

A. When we financed the Central Texas turnpike project, the goal was to absolutely maximize the amount of pavement that we could get on the ground. We stretched the financing to the limit. To do that, what the department did was what’s generally called backstopping, which means we would subsidize the Operations and Maintenance (O&M) expenses for the project until the traffic was high enough to collect enough revenues to where O&M support would no longer be required.

In this financing, the period of O&M support was anticipated to be well in the 20-plus year range, so that if you get traffic that is higher than projected, that means you’re getting more money than you projected. But what that extra money is first doing is lowering the amount of support you’re receiving from TxDOT. That’s not how most roads are financed. That’s not how 183A [Toll] was financed, and that’s not how we’re going to finance any of the other toll roads going forward. This was a very unusual financing because the state felt it was in their interest to maximize the pavement on the ground to make the connections that we’re making.

Q. How is the Central Texas Turnpike System different?

A. This was a 100 percent TxDOT deal, that’s what’s different. When we did this deal, there were three requirements that we had in the bond indenture. One was that we do some interchange improvements to [US] 183 and [Toll] 45.The next requirement was that unless we can’t do it environmentally, we need to construct 183A [Toll]. The third requirement was unless we can’t do it environmentally, we construct [Toll] 45 southeast.

So the 183A [Toll} project was basically set aside for the Central Texas Regional Mobility Authority as their first project. That was a starter kit for the CTRMA. It was environmentally cleared by TxDOT, the counties got together and formed the CTRMA, and so [the 183A Toll project] was given to them and TxDOT delivered the seed money.

Q. How is toll road construction traditionally financed?

A. Very few projects, if any in the entire world, can be financed totally in a traditional manner selling bonds. That means that you are able to, just from the traffic using the road, go to Wall Street and convince them that you would have enough traffic volume that would be willing to pay a high enough price to allow you to go Wall Street and borrow enough money to build the project. Generally, there is always going to need to be some cash involved. So the amount of cash participation may need to be 75 percent or 50 percent or 20 percent. It will vary for each project. Likewise the percent of bond financing will vary. Obviously if you have a project and if you finance that project you’ve got to pay just like the rent on your house or your house bill, you’ve got to pay the banker. You’ve borrowed money and so you’ve got to pay the banker or they get kind of mad at you.

Borrowing money from Wall Street is no different. You have a payment to make for the debt. But what you also have is you have to pay for the operations and you have to pay for the maintenance. Under normal financing what you do is the first dollar you get goes towards operations and maintenance and until you pay for operations and maintenance, a dollar doesn’t work its way to be available to pay for the debt service. And that’s how the bond holders generally like it because even if they don’t get paid, they want that road running and well-maintained or their asset will depreciate and that hurts their ability to ever get money.

Q. How does TxDOT prioritize which projects to do next?

A. That is really the decision of Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization. CAMPO is a federally mandated and created entity. Their principle role is to develop a coordinated multi-modal transportation plan for the region. That’s their charge. And they must develop and approve the list of projects that will go to construction. That list has to include all projects that receive a federal dollar, any federal monies, or are deemed to be regionally significant.

Q. How did TxDOT miscalculate $1.1 billion?