"You want to build a $2 billion toll road? You are going to have to finance it the old-fashioned way, and very conservatively at that."

September 20, 2008

Terry McCrann

The Australian

Copyright 2008

THIS was the week that Wall Street died. In a broader sense it arguably spells the end of American exceptionalism.

Not in the cultural and geopolitical sense in which the term is normally used. That's America not so much the great and powerful, but America the special.

Instead, that America as the home of the world's reserve currency is "excepted" from those normal rules and limitations of international commerce and financial dealing that bind everyone else.

For Wall Street's excesses were really just America's in microcosm. An America that was living beyond its means because it could always "settle the bill" in greenbacks.

And now that Wall Street will arguably be in decline as the world's financial intermediation crossroads, so the US overall will slip as well.

If correct, this week -- perhaps that really should be, this month -- will become the defining end point of the American century. The real entry point to the "21st century"; presumably, China's century.

If so, there'll be an exquisite footnote. The final big event of a week of extraordinary events was the co-ordinated injection by the six major central banks of $US180 billion into global financial markets.

Why co-ordinated? Because it had to be US dollars, provided by the Fed, fed out by the other central banks. And why US dollars? Because as the crisis peaked, everyone wanted greenbacks.

Now this might be seen as proof of that American exceptionalism continuing. I would suggest that it's more its last gasp.

The reason is the interplay between the Wall Street microcosm and the bigger, broader picture you get when you pan back.

Clearly, just at the "Wall Street level", life can't and won't go back to where it was before. After a period of "cleansing", the passage of time and the dimming of memory, the inevitable revival of greed and its sating via sophisticated financial engineering.

This time it really is different. For starters, there are going to be very few players in that future to "go back to". Three of the big five investment banks have gone, Morgan Stanley might follow, to possibly leave only Goldman Sachs.

An investment bank inside a commercial bank won't be able to operate the same way the big five did in the recent past. The precise reason they got into trouble was that they weren't bound by either the bank operating rules in general or bank capital limitations in particular.

The big banks like Citigroup and Morgan had of course followed to some greedy extent. But they were restrained -- saved -- by those rules; and the losses they suffered were survivable. With a little bit of help from sovereign investment funds and the ultimate backstop of Uncle Sam.

So the Wall Street of the immediate to foreseeable future simply won't have the operational structure to go back to a noughties future.

In conjunction, the appetite for -- exotic -- risk is going to be zero, from intermediators and savers alike.

You want to build a $2 billion toll road? You are going to have to finance it the old-fashioned way, and very conservatively at that. Raise $1 billion of real equity and $1 billion of debt secured from banks or a bond issue. No fancy infrastructure trusts with opaque leveraged financing and management contracts.

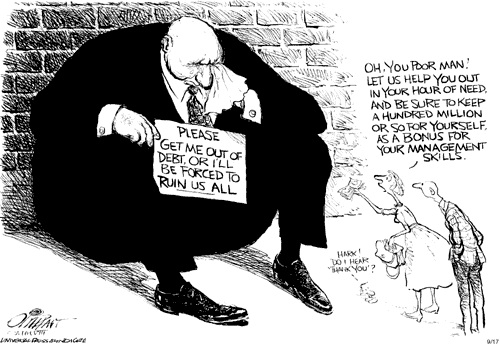

Or do it in the public sector, financed by government borrowing. Either way, having to accept much lower rates of return, much lower growth trajectories. And much lower fees and bonuses to tomorrow's much fewer "masters of the universe".

The same applies across the whole range of exotic structured investments and back into the balance sheets of all financial institutions. Out goes "any three exotic flavours". Back comes plain vanilla.

The broader story is the way Wall Street waxed rich over the last decade -- I would suggest its last great hurrah -- intermediating the dollars earned by the surplus countries back into US investments.

In particular, into US treasuries, funding housing from Fannie and Freddie -- seen by investors as de facto treasuries -- to sub-prime and on to all the exotic structured products.

With some of those dollars dropping also to us down under; and mostly into our housing via the banks and the non-bank securitisers.

It was a not exactly virtuous circle, and perhaps more the mother of all free lunches. The US consumers got cheap Chinese goods, and the Chinese money as well, back to buy or build their houses. And the "masters of the universe" on Wall Street got their ever rising bonuses.

Underwritten ultimately by Alan Greenspan's cheap money policy. Which not only helped feed the appetite for high-yield exotic risk, but also to fund the supply of dollars.

Why did the Government move so quickly to bail out Freddie and Fannie? Sure, because they sat at the centre of the US housing market. Sure, because any major disruption to their activities would have made the last week look calm. And the same applied to AIG.

But a huge factor in the decision was the reality that a very big chunk of their $US5 trillion of securities was held by the Chinese.

That said I somehow doubt they will be quite as willing to go back to "business as usual". This is why this shake-out is going to be very different to all the previous ones. From Enron, the dotcom meltdown, the collapse of Long Term Capital Management, and back to the 1987 crash. Why the end of the great Wall Street investment banks very graphically illustrates the more fundamental termination of Wall Street as the world's financial intermediation and innovation capital.

This will have real and sustained consequences for the US economy. Like Coyote and Road Runner, it's been running on air for some years now.

The most obvious manifestation of that, the sub-prime loans that were underwriting economic activity at the margin; and the easy access by consumers and business alike to borrowing via entities like Fannie and Freddie.

We've had most of the same mix. Cheap Chinese consumer goods. Easy access to -- someone's else's -- money so the household sector didn't have to, and until recently didn't, save. And minor versions of Wall Street's exoticism in Babcock & Brown and Macquarie Bank.

But we also have an economy feeding China's, not just supping on its dollars; a budget in surplus and an official interest rate at 7 per cent against the US's 2 per cent.

All three, much better starting points to face the new world that will continue to emerge. Although that won't help our minor version of Wall Street much.

Although fortunately we didn't breed quite so many investment bankers. Sydney doesn't face quite the terminal future of its bigger cousin.

© 2008 The Australian:www.theaustralian.news.com.au

To search TTC News Archives click

To view the Trans-Texas Corridor Blog click